PURPOSE OF THIS ARTICLE

After the demonstration of the perfect correspondence between rock language (animals & signs) and proto-Sumerian ideographic language in the book :

ADAM (KISH, GIZEH), THE GREAT PREHISTORIC PAIAN GOD or deciphering the language of the caves

This article, also taken from the same book, illustrates this by deciphering the second pettiforme sign on a fresco of a bull in the Marsoulas cave.

This is one of ten examples of deciphering cited in the book, and further proof that the language of prehistory and the most archaic history are one and the same, just like the mythology they convey.

This is in spite of the scientistic theory that still dominates the world of archaeology, phagocyted by a corporatism of researchers who, for the most part, are totally ignorant of the science of archaic linguistics as well as the sacred science of symbolism, and who nevertheless continue, blind among the blind, to monopolize the debate on the meaning to be given to these frescoes.

Table of contents

LINK THIS ARTICLE TO THE ENTIRE LITERARY SERIES “THE TRUE HISTORY OF MANKIND’S RELIGIONS”.

This article is taken from Volume 2, Book 1, also available on this site:

ADAM (KISH, GIZEH), THE GREAT PREHISTORIC PAIAN GOD or deciphering the language of the caves

You can also find this book here :

Already published books

To find out why this book is part of the literary series The True History of Mankind’s Religions, go to :

Introduction / Structure and Content

I hope you enjoy reading this article, which I am making available to you in its entirety.

THE MEANING OF THE SECOND PETTIFORM SIGN IN THE MARSOULAS CAVE

We’ll now turn our attention to another sign that echoes what we’ve seen with the large bison in the Marsoulas fresco.

Evidenciation

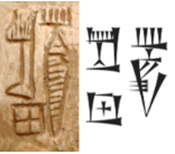

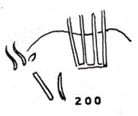

Here are the various signs that André Leroi-Gourhan identifies as also coming from the Marsoulas cave, according to his references (200 and 198).[1]

The sign I’m interested in explaining is ![]() .

.

Please note that it is different from the one already seen ![]() on the fresco of the large Marsoulas panel, since its left tooth is perfectly straight, whereas that of the large Marsoulas panel is curved, which, as we have seen, gives the sign šu or tak.

on the fresco of the large Marsoulas panel, since its left tooth is perfectly straight, whereas that of the large Marsoulas panel is curved, which, as we have seen, gives the sign šu or tak.

What then is the signified of this sign ![]() ?

?

Meaning

In proto-cuneiform

To understand it, I refer you to the proto-cuneiform sign N°20A of the comparative table in the appendix and to its multiple declensions:

![]()

Signs transliterated gal[2] meaning “great, powerful” and designating “a leader”[3] .

This sign is found, for example, in the royal name “Lugal-dalu” in proto-cuneiform script, with the same name in its stylized cuneiform form on the right:

.

According to the CNIL, the ideogram for Lugal is also given for ![]() or

or ![]() [4] and means “a king, a master”.[5]

[4] and means “a king, a master”.[5]

So it’s very simple.

Frankly, you don’t have to be a graduate of Saint-Cyr to realize this, provided you’re familiar with, or even remotely interested in, archaic ideographic scripts.

Proof, if any were needed, of its meaning this time in Hittite hieroglyphics.

Indeed,  is the sign for the Latin dominus, meaning “master”…

is the sign for the Latin dominus, meaning “master”…

So I don’t think it’s worth adding to the list.

Proto-Elamite

This sign is found in proto-elamite in the form ![]() (sign M38a).

(sign M38a).

Even if this script has not been translated, it is almost certain that this sign has the same meaning as in proto-Cuneiform (given the close temporal, cultural and geographical proximity between Sumer and Elam), even if it is not necessarily pronounced the same way.

DECIPHERING THE CAVE FRESCOE REFERENCED N° 200 by A. LEROI GOURHAN

Of course, it’s more than obvious that this sign ![]() applied to the bison

applied to the bison  designates a king, a ruler, a master.

designates a king, a ruler, a master.

This is perfectly in line with what we said earlier, that the primordial father was venerated, adored, deified in the animal form of the wild bull, the auroch, the bison as the father of the gods or the supreme divinity.

Note that this figure ![]() includes not only but also the two horns

includes not only but also the two horns ![]() whose meaning we (now) know (a = father).

whose meaning we (now) know (a = father).

Please also note that the sign ![]() transliterates as giš in proto-cuneiform[6] .

transliterates as giš in proto-cuneiform[6] .

As for the sign of the rib/moon ![]() (ti in Sumerian [7][8] ; spr in Egyptian [9][10] [11] ), this has already been discussed and, as I have already said, it will be shown later, essentially in Part III of Volume 2, how it is the symbol of the wife of primordial man, of primordial woman.

(ti in Sumerian [7][8] ; spr in Egyptian [9][10] [11] ), this has already been discussed and, as I have already said, it will be shown later, essentially in Part III of Volume 2, how it is the symbol of the wife of primordial man, of primordial woman.

So it’s important to realize that if ![]() + bison +

+ bison + ![]() together gives ada am(a) gal: the king/master Adam(a), it’s absolutely, I repeat absolutely remarkable that the ideogram pair

together gives ada am(a) gal: the king/master Adam(a), it’s absolutely, I repeat absolutely remarkable that the ideogram pair ![]() +

+ ![]() means giš-ti, even though gišti is the other Sumerian name for rib, because rib is said “ti” or “gišti”.

means giš-ti, even though gišti is the other Sumerian name for rib, because rib is said “ti” or “gišti”.

Please understand that only ![]() ti the rib could have been ideographed, but by ideographing

ti the rib could have been ideographed, but by ideographing ![]() +

+ ![]() gišti, which is the more complex of the two ideograms used to designate the rib, the authors of this fresco are demonstrating, albeit unwittingly, that it is the proto-cuneiform / hieroglyphic semiological system that they have used here.

gišti, which is the more complex of the two ideograms used to designate the rib, the authors of this fresco are demonstrating, albeit unwittingly, that it is the proto-cuneiform / hieroglyphic semiological system that they have used here.

In fact, the probability that these two logograms, which combine to say gišti, could mean a rib, exactly at the point on the animal’s body that obviously designates a rib, is just zero:

Visual reminder:

This is further proof that we are dealing with the ideographic system that gave rise to proto-cuneiform and hieroglyphics.

DECIPHERING THE MARSOULAS CAFE FRESCOE REFERENCED 138 by A. LEROI GOURHAN

This fresco is simply read as a(da)- gal for the upper part and a(da) še or a(da) eš

Why the intermediate dotted line?

Because the sign from above, a-gal ![]() which means a flood[12] (and is therefore a synonym for father[13] ), but also the father (a) – king/master (gal), is the god from above, the god of heaven.

which means a flood[12] (and is therefore a synonym for father[13] ), but also the father (a) – king/master (gal), is the god from above, the god of heaven.

Whereas under ![]() a(da)eš, he is the father-king-master of the underworld.

a(da)eš, he is the father-king-master of the underworld.

Name, adeš which is, as you may have gathered from pronouncing it, the archaic origin of the name of the future Greek god of the dead, the grave and the underworld, Hades.

REFERENCES AND FOOTNOTES

[1]https://www.persee.fr/doc/bspf_0249-7638_1958_num_55_7_3675 / Le symbolisme des grands signes dans l’art pariétal paléolithique André Leroi-Gourhan ; Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française Année 1958 55-7-8 pp. 384-398

[2] 20A (Falkenstein, 1936, p. 91) (CNIL, 1996?, p. 67)

[3] gal, ñal : n., a large cup ; chief ; eldest son. adj., big, large ; mighty ; great (chamber + abundant, numerous) (A.Halloran, 1999, pp. 30, 31) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: gal, ñal = nominative: a large cup, a chief, an eldest son; adjectives = big, large, mighty (chamber + abundant, numerous)

[4] (CNIL, 1996?, p. 128)

[5] lugal: king; owner, master (lú, ‘man’, + gal, ‘big’) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 62) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: lugal: king; owner, master (lú, ‘man’ + gal, ‘big’)

[6] 3 (CNIL, 1996?, pp. 81, 82)

[7] ti : side, rib; arrow (cf., te, diĥ, and tìl) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 17) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: ti = side, rib, arrow (cf., te, diĥ, and tìl)

[8] Ñišti: strut, brace, rib (‘rib’). (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 148) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: Ñišti = support, brace, rib.

[9] ![]() Crescent moon (also vertical)

Crescent moon (also vertical) ![]() or

or ![]() when used as a determinative); Ideo. or det. in iaH

when used as a determinative); Ideo. or det. in iaH ![]() or ,

or , ![]() moon / Gardiner p. 486, N11.

moon / Gardiner p. 486, N11.

[10] In some inscriptions, ![]() is written for spr

is written for spr ![]() côte / Gardiner p. 486, N11.

côte / Gardiner p. 486, N11.

[11] ![]() Alternative form of

Alternative form of ![]() as in iaH

as in iaH ![]() moon; This sign can be confused with

moon; This sign can be confused with![]() spr coast / Gardiner p. 486, N12

spr coast / Gardiner p. 486, N12

[12]a-gal: overflow of flood waters (‘waters’ + ‘big’) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 72) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: a-gal: overflow of flood waters (‘waters’ + ‘big’).

[13] Volume 4 / Sumerian-French syllabary: a, e4 = nominative; water, watercourse, canal, seminal fluid, descent, father, tears, flood. (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 3)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

See footnotes for each section according to following list :

Proto-sumerian :

CNIL. Full list of proto-cuneiform signs

& Falkenstein, A. (1936). Archaische Texte aus Uruk. https://www.cdli.ox.ac.uk/wiki/doku.php?id=late_uruk_period :

Sumerian :

A.Halloran, J. [1999]. Sumerian Lexicon 3.0.

Heroglyphic:

Faulkner. [reed.2017]. Concise dictionary of Middle Egyptian.

Hiero (hierogl.ch) (Hiero – Pierre Besson)

Proto-Elamite :

The list of Proto-Elamite signs can (normally) be found on the CNIL website:

https://cdli.ox.ac.uk/wiki/proto-elamite#the_corpus

or https://cdli.ox.ac.uk/wiki/doku.php?id=proto-elamite_period

It’s also true, however, that these CNIL links are often dysfunctional.

It is therefore difficult to visualize this list of signs in this way.

A simple and direct way is to go directly to the source from which the CNIL draws this list of signs, namely :

- Meriggi, 1974, La scrittura proto-elamica. Parte IIa: Catalogo dei segni (Rome).

Hittite hieroglyphic :

Mnamon / Antiche scritture del Mediterraneo Guida critica alle risorse elettroniche / Luvio geroglifico – 1300 a.C. (ca.) – 600 a.C.

https://mnamon.sns.it/index.php?page=Scrittura&id=46

https://www.hethport.uni-wuerzburg.de/luwglyph/Signlist_2012.pdf

Archaeology :

Leroi-Gourhan, A. (1958). Le symbolisme des grands signes dans l’art pariétal paléolithique. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française Année 55-7-8 pp. 384-398.

REMINDER OF THE LINK BETWEEN THIS ARTICLE AND THE ENTIRE LITERARY SERIES “THE TRUE HISTORY OF MANKIND’S RELIGIONS”.

This article is taken from Volume 2, Book 1, also available on this site:

ADAM (KISH, GIZEH), THE GREAT PREHISTORIC PAIAN GOD or deciphering the language of the caves

You can also find this book here :

Already published books

To find out why this book is part of the literary series The True History of Mankind’s Religions, go to :

Introduction / Structure and Content

COPYRIGHT REMINDER

As a reminder, please respect copyright, as this book has been registered.

©YVAR BREGEANT, 2023 Tous droits réservés

The French Intellectual Property Code prohibits copies or reproductions for collective use.

Any representation or reproduction in whole or in part by any process whatsoever without the consent of the author or his successors is unlawful and constitutes an infringement punishable by articles L335-2 et seq. of the French Intellectual Property Code.

See the explanation at the top of the section on the author’s policy for making his books available: