PURPOSE OF THIS ARTICLE

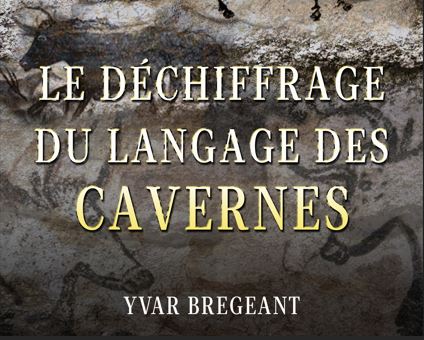

This article helps to demonstrate the perfect correspondence between Upper Palaeolithic rock paintings and the proto-Sumerian or proto-Cuneiform ideographic language.

This demonstration is divided into four parts:

The first part compares around a hundred prehistoric signs, identified and divided into their 25 categories, with identical signs from the proto-Sumerian period. This visual comparison shows that they are extremely similar, and in itself confirms that they are indeed the same writing system.

The second part presents the results of previous research into prehistoric signs.

The third part (previous article) shows the errors and mistakes made by previous researchers on this issue, which prevented them from reaching the right conclusion.

The fourth part (which is the subject of this article) then provides the complete semiological demonstration of the correspondence between the two writing systems, carrying out correctly and exhaustively the comparative background analysis that should have been carried out (comparison of the corpus of signs and semiological rules relating to each system) to arrive at the right result and conclusion: the Upper Palaeolithic rock paintings, with their pairs of images and signs, correspond in every respect to the Sumerian ideographic language and its associated languages (Sumerian, hieroglyphic Egyptian).

Table of contents

LINK THIS ARTICLE TO THE ENTIRE LITERARY SERIES “THE TRUE HISTORY OF MANKIND’S RELIGIONS”.

This article is an excerpt from the book also available on this site:

You can also find this book at the following link :

To find out why this book is part of the literary series The True Stories of Mankind’s Religions, go to page :

Structure and content

I hope you enjoy reading this article, which is available in its entirety below:

Part IV : a genuine and objective analysis of the ideographic languages

In this section, we’ll see that even without knowing either the literal or symbolic meaning of the ideographic languages in question, archaeologists could still have deduced, through a properly conducted comparative analysis of the ideographic scripts of ancient civilizations, that proto-cuneiform had a direct filial link with cave signs.

Since this analysis hasn’t been done, I’ll do it for them in this section.

I will :

-Classify ideographic scripts in chronological and geographical order to identify the most ancient.

– Consider (not a few isolated signs, but) their entire list of signs wherever possible

– Make a comparative analysis of their lists of signs with that of prehistoric signs, to check whether or not the same categories can be found in each.

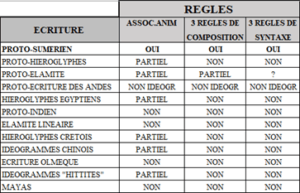

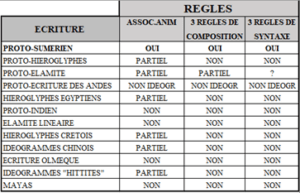

– Compare the operating rules of these languages with those they have observed: sign-animal association; constitution of complex signs; rules of syntax between signs (incompatibilities between signs).

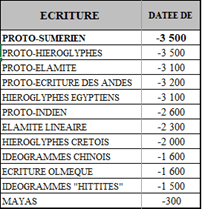

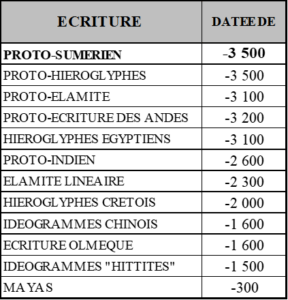

Chronological classification of scriptures

In itself, it’s an aberration to simply mix ideographic scripts, each of which is associated with a perfectly identifiable and datable civilization.

This puts these entries on the same level when they are not.

Let’s imagine that tomorrow we invent a universal ideographic script and turn it into the new Esperanto. Would it also be taken into account simply on the basis of the criterion that it is ideographic?

Obviously, the first thing to do is to classify them by date and prioritize the most archaic to try to match, to get as close as possible to the most archaic meaning. After all, it’s perfectly logical to think that it’s the oldest ideogram’s meaning that’s closest to the truth of its prehistoric counterpart’s meaning.

Now, as we have seen in the retrospective on the six major civilizational centers identified, their birth dates, linked to the appearance of their writing, are known:

Let’s take a brief look at these writings in chronological order of appearance:

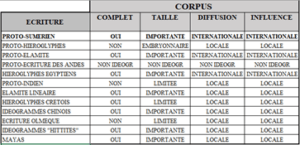

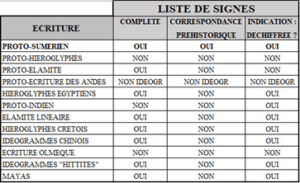

With this table, we can perhaps see a little more clearly how these same authors, who fear the ravages of time, have taken absolutely no account of them in their comparison of ideograms!

From this simple table, we can already see that the two most important scripts are proto-cuneiform and proto-hieroglyphic.

Chronological hierarchization made all the more necessary by the sudden emergence of multiple semiological systems

This temporal classification is all the more necessary if we fully realize that, from the emergence of Sumer and Egypt onwards, a veritable explosion of corpuses with different signs, of new languages throughout the world – a veritable “Cambrian explosion[1] of languages” – took place in a very short space of time compared to later periods.

According to archaeologists, for almost 28,000 years, mankind has had a single, homogeneous semantic system worldwide!

And then, from 3,500 BC onwards, in the space of a few hundred years and/or 1 to 2 thousand years, corpuses with completely different signs appear simultaneously in every geographical area!

Logically, I believe, this explosion of corpora with different signs supports the thesis of a sudden diversification of languages, for, as the authors themselves recognize in their introduction, since the homogeneity of signs in time and space is one of the markers of a semiological system, on the other hand, the sudden loss of this homogeneity and the arborescent multiplication of a multiplicity of different signs is the de facto translation of the emergence of different languages.

So, necessarily, this sudden diversification entails a much greater risk of losing the original community of thought than if the semiological system had remained the same, than if it had remained homogeneous!

This obvious fact, and the far greater exponential risk it entails of losing archaic culture, should have prompted them to prioritize only the oldest archaic system, since later linguistic systems are far more likely to have distanced themselves from the original meaning.

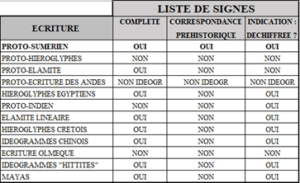

Comparative analysis of the sign lists of the various ideographic languages

Let’s now move on to the second step, which should have been carried out: comparing the lists of signs in known ideographic scripts (which have not necessarily been deciphered) with those of rock art signs.

We’ll be looking at ideographic scripts from the six major civilizations identified (Sumer, Egypt, Indus Valley, China, Central Andes, Mesoamerica): proto-Cuneiform (-3,500), proto-Hieroglyphic (- 3,500), proto-Indian (-2,600), Ossecaille Chinese (-1,600), Olmec script in Mesoamerica (- 1,600).

We’ll also take into consideration proto-Elamite writing (- 3,100), linear Elamite (- 2,300), Cretan hieroglyphs (- 2,000), Hittite (actually Louvite) hieroglyphs (- 1,500) and Mayan writing (- 300).

The aim of these analyses will be to compare the list of signs in each ideographic script with that of prehistoric signs, in order to see to what extent they also use the same categories of signs, with the idea that the one that corresponds most closely is likely to be closely related to it.

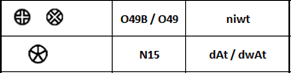

The proto-cuneiform sign list (- 3,500)

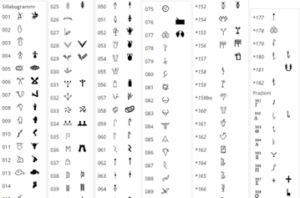

As I indicated in the section “The nature of the ideographic reference script” of the comparative table of a hundred or so signs that I submitted to you in the appendix, this list of signs is available in its entirety at the following two references:

- Adam Falkenstein’s 1936[2] entitled A. Falkenstein, Archaische Texte aus Uruk (Archaische Texte aus Uruk 1; Berlin-Leipzig 1936)[3]

- The so-called “full list of proto-cuneiform signs[4] ” provided by the CNIL, apparently dates back to 1996.

Given that the first list of signs is 216 pages long and the other 346 pages of signs (287 if we consider those referring to logograms, excluding the presentation on pages 287 to 346 of cupules and sticks for their digital use), it goes without saying that I can’t present it in its entirety here.

I urge you to take a look at them, as they’ll help you get to grips with the very special nature of this ideographic language.

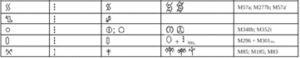

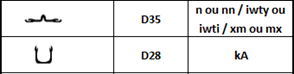

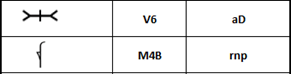

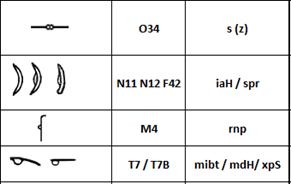

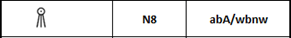

There are some 2,000 proto-cuneiform signs, of which 350 are numerical, 1,100 are individual ideographic signs and 600 are complex signs (combination of 2 or more individual signs).

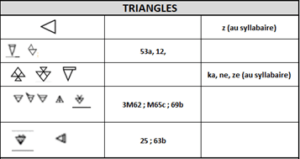

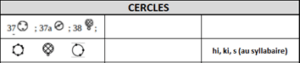

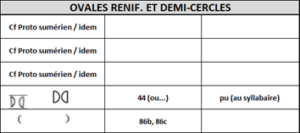

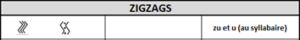

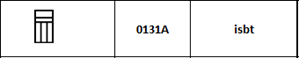

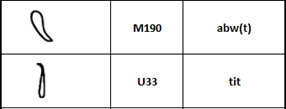

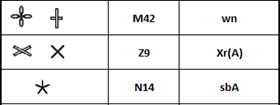

As you can already see from the comparative table, absolutely all the sign categories and sub-categories listed by archaeologists are present in proto-cuneiform.

During your consultation, in addition to the numerous variations of the 9 major sign categories identified by archaeologists, which I have detailed (sub-categorized) in the comparative table, I would like to draw your attention to 3 specific features of proto-cuneiform: clouds of dots, cupules and grooves.

Indeed, the use of these three processes, all of which are found in caves, is truly unique to proto-cuneiform. As we shall see, as an ideographic language, only Proto-Elamite uses cupules, but not lines, clouds of dots or grooves. Proto-Indian uses strokes, but not cupules, clouds of dots and grooves, etc.

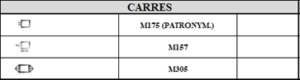

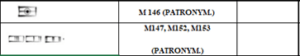

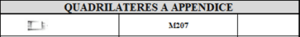

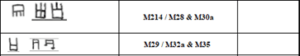

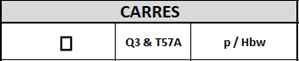

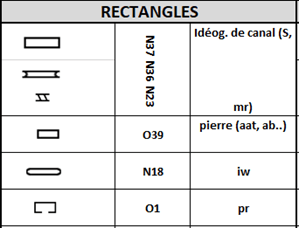

The fact that all the sign categories (e.g. quadrilaterals) and sub-categories (e.g. squares, rectangles, quadrilaterals with appendages…) of prehistoric signs are found in proto-cuneiform, including such highly distinctive ones as cupules, lines and clouds of dots and grooves, is certainly already a very revealing clue.

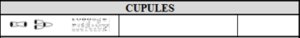

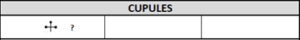

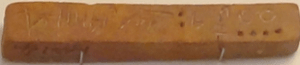

Cupules presentation

On this proto-Cuneiform tablet, you can see cupules: deep circles inlaid in the clay. Bevelled circles can also be considered as such.

Tablet with cuneiform administrative text, Jemdet Nasr, ca 3100-3000 BC. Ashmolean Museum AN1926.602 https://collections.ashmolean.org/object/741775

In Proto-Cuneiform, it should be noted that their use is notably digital.

Indeed, pages 287 to 346 of the CNIL website’s database of proto-cuneiform signs are dedicated to the role of cupules and rods for digital use.

But they can also be used to signify logograms as, for example, with the logograms for :

lam[5] abundance, the underworld or the underworld…[6]

kur[7] the mountain, the underworld…[8]

Cupules are also sometimes integrated into signs, making them a component in their own right:

For example: sila[9] cut, pierce; road; lamb, bait[10] (sila here incorporates a cupule and a chevron.

Point cloud presentation

In our analysis of the rules governing the composition of complex signs, we’ll look at how proto-Cuneiform uses the rule of integration, which archaeologists have identified in numerous examples of signs composed with dots.

Rather than show you these signs here, I’ll let you go to this section of the book to visualize them: integration [in the “Three rules for composing complex signs” section].

Grooves

This is a very special process.

It is to be distinguished from hatching, as grooves are lighter on the surface.

It is regularly found on prehistoric sites.

This is what Genevieve Von Petzinger calls “fingerflutting”.

It’s as if fingerprints or scratches were scratched into the rock surface.

Here is a proto-Cuneiform example of this writing process:

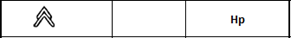

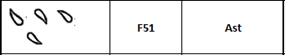

lagab x

You will notice that this right-angled quadrilateral is grooved or as it were scratched, which obviously makes it distinctly different from the same quadrilateral without these grooves, lagab

By way of example, we find the same procedure with the circle :

lagab becomes

lagab x

Now, this transliteration, x, of proto-Cuneiform is, presumably, the corresponding d e of the Sumerian ĥ which is pronounced, as the Arabic ﺥ transliterated as Ḥa, the German ch of ach or the Spanish jota .

This scratching of the rock evokes the guttural “scraping” we make in the throat to evoke this sound.

Purists will call this sound linked to the “x” phoneme a muted velar fricative consonant.[11]

One thing is certain: this writing process is a very special feature unique to both systems.

Access to the list of proto-cuneiform signs unavailable?

Mr. Leroi-Gourhan’s work dates from 1958, and that of G.Sauvet, S.Sauvet and A.Wlodarczyk from 1977, so we can’t say that the 1933 source couldn’t be taken into account.

But perhaps it was harder to find then than now.

As for the second source on the CNIL website, I’m not sure when it was made available (1996?).

In any case, independently of the researchers themselves, I think that given the number of PhD students from the different classes of these researchers, at least one of them could have taken on this research in their place, either because he was encouraged to do so by his thesis professors, or through the fruit of independent personal reflection.

The fact is, neither has happened.

We should seriously ask ourselves why.

The list of proto-heroglyphic signs (-3,500)

This list of signs is very limited, as we saw earlier, to a few signs found on pottery from the Nagada II period in 3,500 BC or 3 animal symbols discovered in 2017 on a cliff near Luxor and dated to 3,250 BC.

Was it possible for our reference archaeologists in 1958 and 1977 to report on this?

I don’t know when the pottery signs were discovered (2001?), but in any case, no. Anyway, the list of signs is so limited that it would have been pointless to compare it with prehistoric signs in order to draw conclusions. Asthe list of signs is so limited, it would have been pointless to compare it with prehistoric signs in order to draw any conclusions.

This is why G.Sauvet, S.Sauvet and A.Wlodarczyk, who are probably unaware of the existence of proto-hieroglyphs, when they note (E) the signs they submit for comparison with prehistoric signs, must understand that these are nothing more than hieroglyphs, dating from – 3,100 at the latest, 400 years after Uruk.

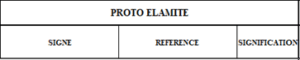

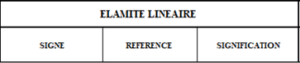

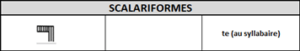

The list of signs for Proto-Elamite (- 3,100) and Linear Elamite (- 2,300)

For ease of processing, we’ll see both lists of signs for these two languages at the same time.

But we must remember that proto-Elamite is, as its name suggests, the older of the two, dating from around – 3,100, while linear Elamite dates back to – 2,300.

It has to be said that none of the signs in the two lists of signs for these two ideographic languages has been submitted by the referring archaeologists. Even though they are much closer to proto-cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs than Cretan or Chinese “Hittite” ideograms.

Moreover, around 170 similar tablets from Uruk V (c. 3,500 BC) in Susa and a few other sites in Iran, such as Tepe Sialk, are considered pre-Proto-Elamite, albeit with similarities to proto-Cuneiform.

And yet, unlike protohieroglyphs, a complete list of signs exists for proto-Elamite. And so does the later linear Elamite.

The list of proto-Elamite signs can (normally) be found on the CNIL website[12] :

https://cdli.ox.ac.uk/wiki/proto-elamite#the_corpus

or https://cdli.ox.ac.uk/wiki/doku.php?id=proto-elamite_period

It is also true, however, that these CNIL links are often dysfunctional.

It is therefore difficult to visualize this list of signs in this way.

A simple and direct way is then to go directly to the source where the CNIL will draw this list of signs, namely essentially :

- Meriggi, 1974, La scrittura proto-elamica. Parte IIa: Catalogo dei segni (Rome).

So as not to leave you without a means of comparison in this book, I will provide you with links to :

- A brief overview of the main signs of proto-elamite

- A table comparing proto-elamite and proto-cuneiform

- The table showing the first comparison of similar signs between proto-elamite and linear elamite

- Two further comparison tables between proto-elamite and linear elamite

with a table of identical signs and another of similar signs

- A table comparing complex signs between proto-elamite and linear elamite

- A table of patronymic signs in Proto-Elamite.

In submitting these tables to you, I would like to make it clear that I am not presenting the entire list of proto-elamite signs, but only those that are identical or similar to linear elamite.

The Proto-Elamite sign list contains some 1,900 non-numerical signs.

That’s a lot, but there are two things to bear in mind:

While so many signs were identified, only a small group of signs were used across all text types. A statistical study carried out on the frequency of Proto-Elamite signs even suggests a statistical distribution similar to that of Proto-Cuneiform[13] .

In proto-cuneiform, too, the same signs are often used, although the list of signs appears to be very extensive.

The presentation that follows simply kills three birds with one stone, as it allows you to visualize ..:

- The proximity of proto-Elamite to the older proto-cuneiform

- The proximity of linear elamite to older proto-elamite

- Signs of proto-elamite and linear elamite

Below you will find links to the tables in the headings:

A brief overview of the main signs of proto-elamite:

https://cdli.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/articles/cdlb/2002-1.pdf

Proto-Elamite Sign Frequencies / Jacob L. Dahl / University of California, Los Angeles /

If you’ve taken a close look at the proto-Cuneiform lexicon, you’ll have noticed that many proto-Elamite signs are similar, if not identical:

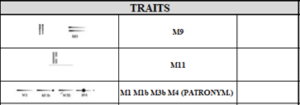

For example, you will find the signs M1 , M9

, M36

, M157

, M218

, M297

, and the cupules M388

.

Analogies between Proto-Elamite and Proto-Cuneiform sign lists

Researchers such as Robert Englund have made initial comparisons between these two languages. His comparative table was taken up by François Desset in one of his articles:

https://www.persee.fr/doc/arnil_1161-0492_2016_num_26_1_1104

Graphical (and semantical?) correspondences between protocuneiform and PE signs and numerical systems used to account for them (from Englund 2004a: fig. 5.14) / 68 archéo-nil n° 26 -juin 2016 François Desset.

Of course, the similarities observed do not necessarily mean that the meaning was strictly the same in both languages.

But it does allow us to grasp the idea that these two semiological systems were close, with the particularity that proto-cuneiform was the more archaic.

The authors’ distinction between proto-Elamite and linear Elamite

It is interesting to note that the source providing the first table states that “the repertoire of signs in the much later script known as Linear Elamite bears no resemblance to Proto-Elamite; the few ideograms are graphically as close to the signs of Chinese oracle inscriptions (i.e. the archaic Chinese Ossecaille script) as to the much older signs of Proto-Elamite”.

As we’ll now see, this isn’t true, because in 2020 a more serious comparison showed a high degree of similarity between many of the signs in these two lists of writing signs.

These are the comparative tables from this 2020 study, which I’m linking to here, because it also has the merit of showing us signs of both scripts simultaneously.

The table of the first comparison of similar signs between proto-Elamite (PE) and Linear Elamite (LE) by P. Merigi

In the following link, you will find a first comparative table in the left-hand columns of the signs of linear elamite for which P. Merigi (1971) had identified similar signs in proto-elamite:

https://center-for-decipherment.ch/pubs/Mäder%202020__Proto-_und_Linear-Elamisch.pdf

Following this table are the signs of linear elamite for which P. Merigi did not identify an analogy in proto-elamite:

So we know all the simple signs of linear elamite.

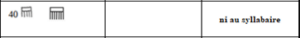

Table of signs for Linear Elamite

For your information, you will find at the following link a table of signs or syllabary, made by F. Dresset, indicating to which logograms different ideograms refer:

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wikiélamite_linéaire#/media/Fichier:Linear_Elamite_alpha-syllabary.jpg

Further comparison of Proto-Elamite and Linear Elamite signs

The above-mentioned 2020 study, which cites P.Berigi’s first comparative work of 1971, goes on to make a more exhaustive comparison (including signs that have since been discovered), eventually highlighting the identical signs in both lists of signs, their similar signs, and then also a comparison of their complex signs.

Proto-Elamite patronymic signs

For your information, the following link also contains an inventory of patronymic signs (personal names), which were composed using nearly 200 simple signs:

https://www.persee.fr/doc/arnil_1161-0492_2016_num_26_1_1104

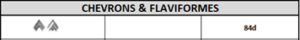

Comparison of proto-elamite and linear elamite sign lists with cave signs

The question we’re going to ask ourselves is whether, as with proto-cuneiform, we’ll find all the prehistoric sign categories in proto-Elamite or linear Elamite?

Let’s see what the comparison gives for proto-elamite and then for linear elamite:

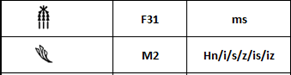

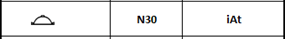

the proto-elamite sign list:

A quick look reveals that the preferred geometric shape is the rhombus.

Here is the result if we carry out a precise and exhaustive comparison to determine which prehistoric sign categories are represented in proto-cuneiform signs (see previous tables):

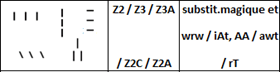

Signs categories represented:

(see 1er comparative table and table of patronymic signs)

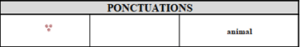

Punctuation: punctuation is only present in certain compound signs:

Linear Proto

Signs categories not represented:

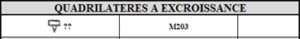

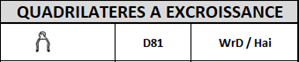

Quadrilateral with outgrowth; see possible sign below:

Reniformes

Tectiform; however, see possible signs below:

Sticks: hatching is sometimes found within complex figures, but we can’t speak of sticks. Cupules seem to fulfil the numerical role of sticks in elamite.

Grooves: there are none, unless you consider that certain zigzag signs superimposed on figures can play this more archaic role.

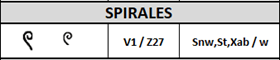

Spirals

the list of elamite signs:

A quick look reveals that the unquestionably preferred geometric shape is the rhombus.

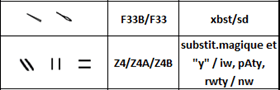

Careful comparison with prehistoric signs shows that :

Signs categories represented :

Punctuation: punctuation is only present in :

Linear Proto

Signs categories not represented:

Squares

Rectangles

Quadrilateral with outgrowth

Possible Elamite version of gum proto-cuneiform itself being a variant of the prehistoric (peitzinger)

? or

(sauvet)

Reniformes

Arrows

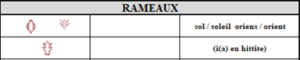

Branches

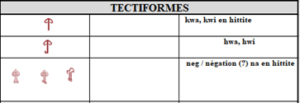

Tectiformes

Sticks: hatching is sometimes found within complex figures, but we can’t speak of sticks. Cupules seem to fulfil the numerical role of sticks in elamite.

Grooves: there are none, unless you consider that certain zigzag signs superimposed on figures can play this more archaic role.

Spirals

Conclusion on proto-elamite and linear elamite

We can see that proto-Elamite and linear Elamite do not contain all the prehistoric sign categories found in proto-cuneiform.

However, proto-Elamite, because of its proven borrowings from proto-cuneiform and its proximity (semantic, geographical, temporal), and, by extension, linear Elamite, because the latter probably derives from proto-Elamite, are both scripts likely to corroborate or shed light on explanations of certain prehistoric signs in support of proto-cuneiform.

However, as it has not yet been deciphered, it cannot yet be of any use in this respect.

Let us note in passing, even if it is not the object of this analysis and of this book, that proto-cuneiform should make it possible to decipher or approach the meaning of some of the signs of the proto-Elamite by comparing those identical or very similar to its own.

This doesn’t mean that the pronunciation was the same, since it was obviously a different language, but being able to contextualize the meaning of each sign is an essential step towards deciphering it in the sense of transliteration into phonetized logograms.

The list of Andean signs (- 3,200)

Even if this language is dated as being as old as hieroglyphs, it cannot be included in this study, as we are only interested in archaic, or even ancient, ideographic languages.

As you can easily understand, this language is conveyed by knots, so there can be no question of ideographic writing that could be compared with prehistoric signs.

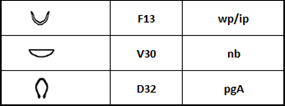

The list of Egyptian hieroglyphic signs (- 3,100)

It is fully accessible here:

https://www.hierogl.ch/hiero/Hiero:Tous_les_signes

Here’s the result if we carry out a precise and exhaustive comparison to determine which categories of prehistoric signs are represented in Egyptian hieroglyphic signs:

Sign categories represented:

In addition to these categories of signs, there are also sticks or scepters, harpoons and a serpentiform.

Unrepresented signs categories:

While many categories are represented, there are no :

Quadrilateral with appendix

Pettiformes

Grilles

Triangles

Reniformes

Sticks

Punctuations

Cupules

Grooved.

Conclusion on the list of hieroglyphic signs

Hieroglyphic signs, like proto-cuneiform, do not contain all the categories of prehistoric signs.

It is, however, a language whose close proximity to Sumerian may corroborate or even explain certain prehistoric signs in support of proto-cuneiform.

In this and subsequent books, we’ll have the opportunity to see the many ways in which hieroglyphics and Sumerian are intertwined, so that Sumerian will prove to be the key to deciphering the mysticism concealed in hieroglyphic Egyptian. Conversely, we’ll regularly see how hieroglyphic Egyptian helps to illustrate, corroborate and even illuminate parts of the symbolic system of the original false universal religion.

The list of proto-Indian signs (- 2,600)

This list of signs exists, but the language has not yet been deciphered.

Here is a list of its signs, based on Mr Brozny’s deciphering efforts in

1,940[14] :

The complete repertoire of Proto-Indian signs includes 400 to 450 simple or compound signs, with variations[15] .

The fact is, I haven’t been able to access the entire list of signs.

On the basis of this syllabary, which at first glance seems to list all the basic signs, let’s see whether all the categories of prehistoric signs are represented or not.

Sign categories represented:

You’ll find :

- Rectangular quadrilaterals

,

- Quadrilaterals with appendages

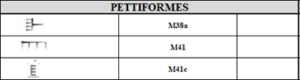

- Pettiformes :

,

,

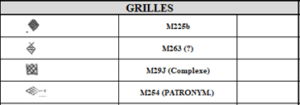

- Grids:

?

- Scalariformes:

?

- Quadrilaterals with protrusions :

,

- Claviformes :

,

,

,

,

,

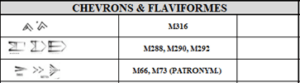

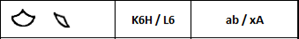

- Chevrons :

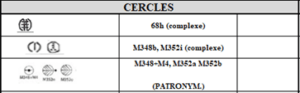

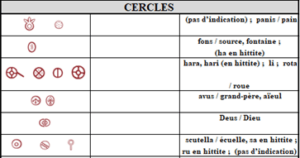

- Circles :

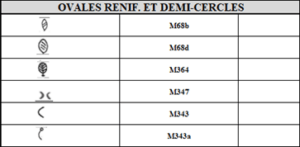

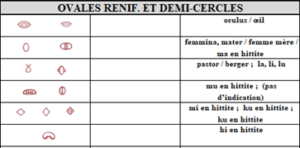

- Oval :

,

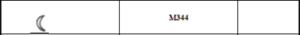

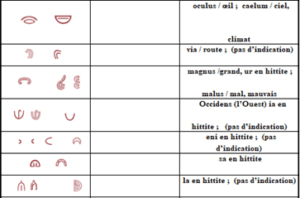

- Half circles :

,

,

,

,

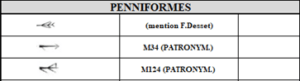

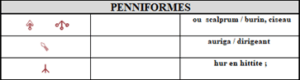

- Penniformes :

- Tectiformes:

?

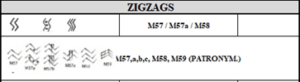

- Zigzags:

?

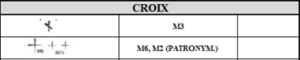

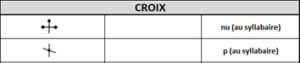

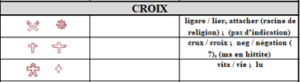

- Cross:

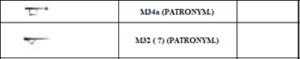

- Sticks :

,

,

,

,

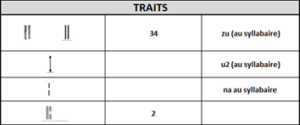

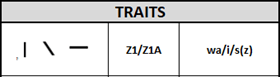

- Traits :

,

Sign categories not represented:

While many categories are represented, there are no :

- Square quadrilaterals

- Triangles

- Reniformes

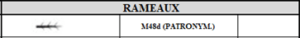

- Branches

- Punctuations

- Cupules

- Splines

- Spirals

Conclusion on the list of proto-Indian signs

We note that the proto-Indian signs (available) do not contain all the categories of prehistoric signs, like the proto-cuneiform.

We can also see that a large number of categories are represented, with signs that closely resemble those already found in proto-cuneiform.

It’s a language whose signs are visibly close to those of Proto-Cuneiform (and even Proto-Elamite), demonstrating the common origin of the same sign system in this region of the world originally dominated by Proto-Cuneiform.

It therefore appears likely to corroborate or even explain certain prehistoric signs in support of proto-cuneiform.

However, as it has not yet been deciphered, it cannot yet be of any use in this respect.

As in the case of Proto-Elamite, it should be noted in passing – even if this is not the object of this analysis and of this book – that Proto-Cuneiform should make it possible to decipher or approach the meaning of some of the Proto-Indian signs by comparing those identical or very similar to its own. This does not mean that the pronunciation was the same, since it was obviously a different language, but being able to contextualize the meaning of each sign is an essential step towards deciphering it in the sense of transliteration into phonetized logograms.

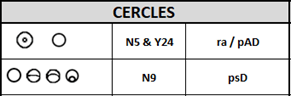

The list of signs in cretan hieroglyphs (- 2,000)

Here’s what you can read about them:

An inventory of symbols was drawn up by Evans in 1909, by Meijer in 1982, and by Olivier and Godart 1996 (the CHIC). ” … ” The glyphs listed by CHIC include 96 syllabograms, representing sounds, ten of which are also logograms, representing words or morphemes.

There are also twenty-three logograms representing four levels of numbers – units, tens, hundreds and thousands – as well as numerical fractions, and two types of punctuation.[16] .

Here is an example of the obviously exhaustive (to date) list of signs[17] :

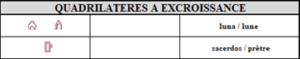

Here’s the result if we carry out a precise and exhaustive comparison to determine which categories of prehistoric signs are represented in Cretan hieroglyphic signs:

Sign categories represented:

Rectangular quadrilaterals: 056,

076 ?

163

Quadrilaterals with appendages: 41

Pettiformes: 6 ?

26 ?

28 ?

158 ?

Grids: 39

Quadrilaterals with protrusions: 076 ?

Claviformes: 62

63

64

177

65

304 ? (fraction)

Chevrons: 305 ? (fraction) & Flaviformes:

93

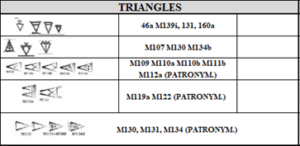

Triangles: 85,

72

Circles: 75,

47,

73,

170

Oval : ,

153

Half-circles: 81?

Penniformes: 50,

51

176 (logog.)

Branches: 25,

26 ?

27 ;

28 ?

29

158 ?

30

Tectiformes: 37 ?

84

172 ? (logog.)

Zigzags: 61,

69

Cross: 307,

70

Sticks: 100 (fraction)

Punctuations: 75 ? number 10

Cretan hieroglyphs (between -1900 and -1600) on a piece of clay, found in Malia or Knossos, Crete. The dots represent numbers. Artefact on display at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum[18] / Y-barton – Personal work

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hiéroglyphes_crétois#/media/Fichier:Cretan_hieroglyphs2.png

Features: 66,

67.

Sign categories not represented:

While many categories are represented, there are no :

Square quadrilaterals

Scalariformes

Reniformes

Cupules

Splines

Spirals

Conclusion on the list of signs in Cretan hieroglyphs

We note that the Cretan signs (available) do not contain all the categories of prehistoric signs, like proto-cuneiform.

As in the case of Proto-Indian, we can also observe that quite a number of categories are represented, with some signs showing a certain similarity to those already found in Proto-Cuneiform.

It’s a language associated by some linguists with Hittite, with the hypothesis of a common origin from Syria.

This suggests the common origin of the same sign system in this region of the world, originally dominated by proto-cuneiform.

It appears likely to corroborate certain prehistoric signs in support of proto-cuneiform. However, as it has not yet been deciphered, it cannot yet be of any use in this respect.

As in the case of proto-Elamite and proto-Indian, although this is not the object of this analysis and this book, proto-Cuneiform should make it possible to decipher or approach the meaning of some of the Cretan signs by comparing them with those similar to its own.

As with previous writings, I should point out that this does not mean that the pronunciation was the same, since it was obviously a different language, but being able to contextualize the meaning of each sign is an essential step towards deciphering it in the sense of transliteration into phonetized logograms.

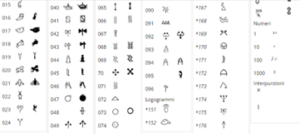

The list of chinese ideographic signs (- 1,600)

Here’s what[19] has to say about China’s most archaic ideographic script, the ossecaille:

Ossecaille writing is a Chinese script used from the 15th to the 10th century B.C. on bones or scales. According to the Great Ricci, Shang scribes (15th century B.C.) sometimes marked characters that were later engraved.

Numerous inscriptions were discovered by Chinese scholar Wang Yirong at the end of the 19th century, engraved on animal bones gǔ, most often bovine shoulder blades (scapulomancy), and on tortoise shell jiǎ[20] from the carapace plastron (plastromancy), hence its name by the Chinese as jiǎgǔwén writing, literally “ossecaille writing”.

Around fifty thousand inscriptions are known, comprising six thousand signs, a third of which have been deciphered. These inscriptions are brief, the longest text, on a bovid shoulder blade, comprising around one hundred signs. The scholar Dong Zuobin (1895-1963) was the first to periodize these inscriptions and distinguish between different schools of scribes.

Most of the inscriptions found are divinatory bǔcí, which is why they are often referred to as divinatory or oracular inscriptions. Later, however, it was realized that some had nothing to do with divination at all, and so a distinction was made between divinatory bǔcí inscriptions and non-divinatory fēibǔcí inscriptions.

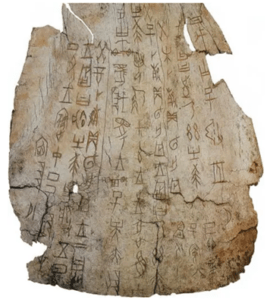

Here is an example of a bovine shoulder blade engraved with these signs[21] :

I won’t hide my difficulty in accessing a complete list of the signs found.

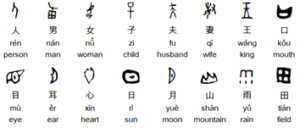

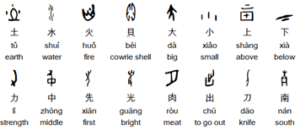

I was simply able to find these few major signs:

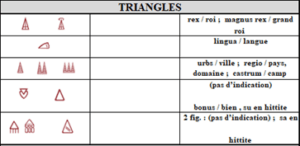

Here’s the result if we do a simple comparison to determine which categories of prehistoric signs appear to be visibly represented in Chinese ideographic signs:

Sign categories represented:

(In the following list of signs, the indication of phonic intonation in the transliteration of the signs is not correctly respected)

Square quadrilaterals: tian champ,

nan homme

zi enfant

Rectangular quadrilaterals: shang above

Pettiformes: yu rain

Grids: ? tian champ,

nan homme

Claviformes: and ear

Rafters: ba 8

Triangles: wu 5

shi 10

Circles: ri soleil,

mu œil

Oval: kou bouche,

tu terre,

Half circles: yue lune

Palm branches: fu mari, da

gros, niù

vache

Tectiformes: ? liù 6

Cross: zi child

Sticks: yu rain,

tu earth,

shui water,

xiao small

Traits: yi 1,

er 2,

san 3,

si 4

Spirals: (see example)

Sign categories not represented:

While many categories are represented, there doesn’t seem to be a :

- Quadrilaterals with appendages

- Scalariformes

- Quadrilaterals with protrusions

- Reniformes

- Penniformes

- Zigzags

- Punctuations

- Cupules

- Splines

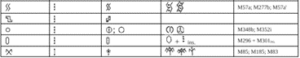

Analogies between Sumerian, hieroglyphs and bones

I’d like to draw your attention to a number of similarities between ossicles and Sumerian or hieroglyphs:

The water

Note the ideographic proximity between the Sumerian sign for a water[22] and the Chinese shui

sign water, with its characteristic central line break evoking a watercourse.

The mouth

In ossecaille, the oval is the ideogram for the mouth (kou mouth), as in hieroglyphic r

mouth[23] .

The field

There is an ideographic proximity between the ossicle: champ tian champ with the proto-Cuneiform ideogram agar

champ and also with the hieroglyph

[24] (a Land demarcated by irrigation streams), which is notably used as a determinative of garden as in Hsp

garden

The man

There is an ideographic proximity between the ossecaille: nan man and the Sumerian udu

or ud

which, while in Sumerian literally designating a sheep, a ram, small cattle[25] , has as its symbolic meaning the sun ud, u4[26] and through him, the great deity who, as we shall see, is none other than the first deified man.

The very fact that nan, man, is composed with the ideogram field tian is in line with Sumerian (and almost universal) symbolism, where the field is a symbol of the female genitor, the furrow of the earth her vagina, the man as ploughman with his plough and sower, the progenitor with his phallus pouring out his seed[27] .

In Sumerian, agarin2,3 , for example, refers to a father, mother, womb or uterus [28]

This fertile “field” symbolizing the “fertile woman” is the deeper meaning of the name Hagar, Abraham’s concubine who gave him Ishmael, the ancestor of the Arab nation.

The sun

There is also an obvious ideographic (and semantic) proximity between the ri ossecaille sun and the Egyptian hieroglyph for the sun

which serves as a determinative for ra

the sun, the day[29] .

Remember that this ra is none other than one of the first signs that Champollion deciphered in a cartouche, enabling him to understand that it referred to the god Ra.

Let’s therefore understand that beyond the literal meaning of “sun”, this sign also and above all designates the great divinity, the first deified ancestor.

The earth

In the same vein, there is also a certain semantic proximity between the ossecaille earth tu and the hieroglyphic earth tA

earth, terrestrial world [30]

The mother

Mother’s ossecaille ideogram is mǔ [31]

Now, in Sumerian, mu designates a woman, a female[32] .

The semantic proximity is obvious.

But note also, and more importantly, that the mǔ ossécaille is homophonous with the ossécaillle mu eye .

This is a highly revealing clue to the universality of Sumerian religious mysticism, whose profound influence can be seen in the writing, since I’ll have a chance to demonstrate that the mother goddess was notably worshipped as the goddess of the eye.

There are several reasons for this, which I can’t go into here.

But if we limit ourselves to the semantic reason, in sumerian igi means an eye, a face and also a glance[33] . Since igi means a glance, it’s also related to ug6, u6 (ideogram igi.é; contraction of igi “eye” and é “house, temple…[34] “) which also means “astonishment, glance, glance”.

Now, ug or ugu carries the meaning of a natural, biological, genetic ancestor.

In fact, ugu4 (corresponding to the ideogram “ku“) has the verbal meaning of “to bear, procreate, produce”[35] . This same ugu4 with its equivalent ùgun also has the verbal meaning of “to beget, to bear”, the nominative meaning of “an ancestor”, an ancestor from whom we inherit the genetics[36] .

The term ama-ugu, which combines the terms mother “ama” and “ugu“, means a natural or biological mother[37] . “úgun” designates a lady, a leader[38] . a-ugu4 (also with the ideogram “ku”) means “the father who begat someone”[39] .

We also note that a-ka is a strict equivalent of “úgu“.[40]

And if we take “ig” alone (i.e. not igi, but ig) it means a door[41] , and is then a strict equivalent of “ aka4″ which also means “a door[42] “.

In Sumerian, therefore, there is an association between the eye on the one hand and the procreative genitrix on the other, through the play of equivalences between the logograms ig(i) / ugu/aka.

What does this mean? That the homophonic (figurative, symbolic) association of mother-eye ossecaille with the logogram “mu” is basically exactly the same, albeit pronounced differently (and then again, mu is also Sumerian!) as the Sumerian association with igi.

Above all, we can see that the sumerian and ossecaille languages were underpinned by the same mysticism.

Conclusion on the list of signs of Chinese ossecaille idéograms

First of all, as the list of signs is very incomplete, it’s not possible to be definitive, but it seems that ossecaille chinese signs do not contain all the categories of prehistoric signs found in proto-cuneiform.

In view of the signs observed, it seems unlikely that, for example, clouds of dots, cupules and grooves are an integral part of this sign system.

We can also see that a wide range of categories are represented, with signs that bear a certain resemblance to those already found in proto-cuneiform.

We can also see that while the phonetics are different, there are obvious figurative and symbolic analogies, with the same associations based on the same principle of homophony.

This brief analysis also leads to the conclusion that, even if different signs were eventually chosen by these two semiotic systems far apart in time and space, there are still indications of the influence of proto-cuneiform on this script (since proto-cuneiform is more archaic).

It would therefore be interesting to have access to the complete set of Ossecaille signs for a more exhaustive comparison, not in order to decipher them, since this is already known, but to gain a better understanding of just how close the Chinese conceptual framework was to proto-Cuneiform. Let me be clear: conceptual framework, because even if the pronunciation is completely different, there are obvious conceptual analogies, and it’s these that interest us in corroborating the deciphering of figurative, symbolic language.

The list of signs of the Olmec script (- 1,600)

Here’s what you can read about these signs[43] :

Olmec hieroglyphs are a pictographic writing system dating back to at least 650 BC, used by the Olmec civilization.

Caterina Magni mentions the existence of glyphs, notably on Stele 13 at La Venta. She points to the existence of a cylinder seal from Tlatilco dating back to 650 BC, which, according to some scientists, already bears witness to the existence of a form of writing. Then, with the discovery of the Cascajal Stele, specialists began to agree that writing was finally identifiable in the Olmec culture.

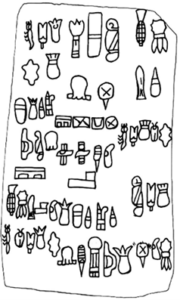

The Cascajal stele is a stone discovered in Mexico in 1999 and studied from 2005 onwards. It is believed to bear the oldest writing discovered in the Americas.

Here is a survey of the Cascajal stone with its 62 signs[44] :

The corpus of signs in Olmec script is therefore very limited, and the list of available signs is potentially even more so.

This lack of signs can be put into perspective, however, because if we examine the Carajas stele and its 62 signs, 19 of them are strictly identical and repeated between 2 and 4 times:

4 x ; 4 x

; 3 x

; 3 x

; 3 x

; 3 x

; 3 x

; 3 x

; 3 x

; 2 x

;

2 x ; 2 x

; 2 x

; 2 x

; 2 x

; 2 x

; 2 x

; 2 x

; 2 x

.

That’s 19 repeated signs out of 62, leaving only 13 unrepeated signs, for a total of 32 signs.

The repetition of signs in such a short space of time points to an ideographic script similar to our alphabetic system.

In fact, there are sometimes sequences of identical “syllables”. Note the first two signs of and

There are also sequences of similar “signs” with, for example, the same 4 signs used in 2 different “words” of 5 “signs” each: and

So this list of signs is clearly not as incomplete as it seems.

With what we have, let’s ask ourselves whether the different categories of prehistoric signs are represented or not:

Sign categories represented:

Square quadrilaterals :

Rectangular quadrilaterals :

,

Quadrilaterals with appendages :

Grids :

Scalariformes: ?

Claviformes :

Triangles :

Circles :

Oval :

Reniformes :

Tectiforms :

Cross:

Sign categories not represented:

While many categories are represented, there doesn’t seem to be a :

Pettiformes

Quadrilaterals with protrusions

Chevrons

Half circles

Penniformes

Branches

Sticks

Punctuations

Features

Cupules

Splines

Spirals

Zigzags

Analogies between proto-cuneiform, proto-elamite and olmec

In passing, we note the similarities of the following signs

with proto-Cuneiform and even proto-Elamite signs (

)

Concerning , we have already observed that in Sumerian ud

(see also

[45] and so reversed ) if it literally designates in Sumerian a sheep, a ram, small cattle[46] , its symbolic meaning is the sun ud, u4[47] thus alluding to the great divinity.

It’s logical that this sign was widely used (albeit slightly altered) to designate the great divinity associated with the sun.

Conclusion on the list of Olmec ideogram signs

As we’ve seen, the list of signs is potentially incomplete, but in the face of what strongly resembles an alphabetic system, there’s little chance of finding a mass of very different additional signs, should the corpus be expanded by new archaeological discoveries.

As it stands, Olmec ideograms clearly do not contain all the categories of prehistoric signs found in proto-cuneiform.

Some categories are represented, and some signs show a certain similarity with proto-cuneiform, notably the ud/u characteristic of the great divinity.

This brief analysis also leads to the conclusion that, even if different signs were eventually chosen by these two semiotic systems far apart in time and space, there are still indications of the influence of proto-cuneiform on this script (since proto-cuneiform is more archaic).

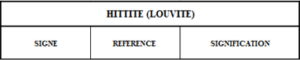

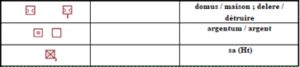

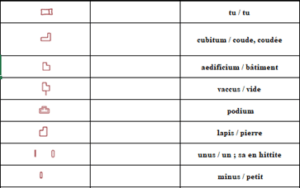

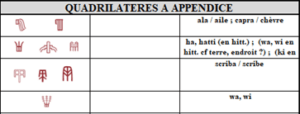

The Hittite (Louvite) list of ideographic signs (- 1,500)

As explained in the section “Why Sumer is the most archaic civilization”, when we talk about Hittite ideograms, we are referring to the Hittites’ late use of hieroglyphs or ideograms of their own “invention” around 1500 BC to transcribe a Louvite dialect[48] .

In earlier times, Hittite (corresponding to Nesic/Nesite, as the capital was Nesha) and Hatti were written in cuneiform, while Louvite was written in Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Here’s what you can read about the Hittite/Luvite ideograms specific to this culture: :

Hittite hieroglyphs form an original writing system used mainly in monumental inscriptions, for writing a dialect of Louvite.

This hieroglyphic script seems to be an original creation of the Louvitolian-speaking peoples of Anatolia, and the signs bear no relation to Egyptian or Cretan hieroglyphs.

The earliest known inscriptions date from the 15th century B.C.; this is particularly late, as Louvite had by then been written for several centuries using the cuneiform script of Mesopotamian origin. The most recent inscriptions date from the 7th century BC, shortly after the fall of the last Neo-Hittite kingdoms.

Hittite hieroglyphs, which were deciphered in the 20th century, are made up of two groups of signs: ideograms and syllabic signs.

As in the cuneiform system, each sign can combine both ideogrammatic or, in today’s terminology, logogrammatic and syllabic values. In addition, certain signs with logogrammatic value are used as determinatives, i.e. they determine the category of the word that follows or precedes it: a name of a person, a deity, a city, etc., for example.

They represent either figurative drawings, such as animals or members of the human body, or simple or more complex geometric figures.

This list of signs[49] is perfectly accessible:

Go to: https://mnamon.sns.it/index.php?page=Scrittura&id=46

And to: https://www.hethport.uni-wuerzburg.de/luwglyph/ –) sign list

There are 19 pages of signs (with Latin naming) that I cannot objectively insert here.

Here is an example of what page 2 looks like:

Note that the meaning of the sign is given in Latin and its pronunciation, when known, is given in Hittite/Louvite.

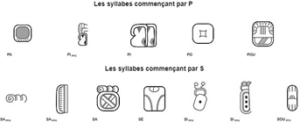

Here’s the result if we do a simple comparison to determine which categories of prehistoric signs appear to be visibly represented in Hittite ideographic signs:

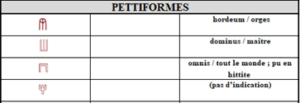

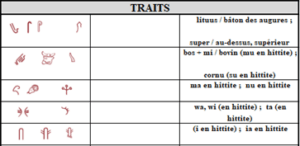

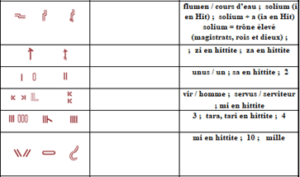

Sign categories represented:

Sign categories not represented:

Scalariformes

Cupules

Splines

Spirals

Examples of additional sign categories :

Analogies between Hittite and Sumerian and hieroglyphs

With sumerian

Examples that illustrate a close relationship with Sumerian and certainly distant borrowings (all the more so as Sumerian cuneiform was for a long time the means of writing used by the Hittites before they created their own hieroglyphs) include the following:

a/i: le cours d’eau / le père-dieu

The fact that the watercourse i [50] is also represented in this language by the same sign as the proto-cuneiform a

[51] or

Add to this the fact that in Sumerian, the phoneme “i” also means a watercourse by i7[52] .

In this way, both the ideogram and its phonetization convey the same idea.

What’s particularly interesting is that in Hittite, this apparently simple “watercourse” is actually much more than that, since associated with the phoneme “a”, it signifies an elevated throne, symbolically the supreme power of the great divinity. However, in Sumerian, “a” also means father, which, as we’ll see more fully in Part II, was used to designate the first man of mankind, the primordial ancestor, the father of humanity who was elevated to the rank of father of the gods upon his death.

The leader, the master:

The Hittite ideogram for master: [53] is very similar to the proto-Cuneiform gal

[54] (usually translated as great, but), which also means a chief.[55]

The great

The Hittite ideogram ur [56] for “great” can also be associated with the Sumerian ur (which has a very rich and profound meaning).

Let’s just say that in Sumerian, this logogram ur has the meaning of surrounding[57] (with the symbolic meaning of protecting), which the Hittite ideogram clearly evokes, and also that of someone strong, powerful, intelligent[58] , the characteristics of a leader, hence the relationship that can be made with both the ideogram and its Hittite meaning.

With the egyptian

It’s also worth noting that the Hittites gave themselves this name by no means by chance.

This name comes from the word Hatti, which was that of their main kingdom, transcribed by the Hittite ideogram ha, hatti :

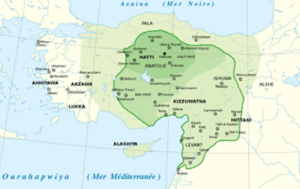

Here’s a map of their area of influence, with the Hatti kingdom in the center.

Map of the Hittite Empire in its widest extent, with the Hittite heartland c. 1350-1300 BC represented by the green line.[59]

This word, Hatti, is pure Egyptian.

Indeed, HAt-a means the beginning, beginning[60] ; HAty-a designates the monarch, the best, the first[61] .

So it’s easy to understand that the choice of this word was made out of a desire to place oneself in the direct spiritual and biological filiation of the first man, the father-ancestor, who became father of the gods, and who was, as we’ll see in Part II, the first king, ruler, monarch.

Like the Pharaohs, who saw themselves as the reincarnated sons of the father of the gods, Ra, and by extension, all the Egyptian people, the Hittites too, by choosing this name, claimed the same type of filiation, in line with the greatest of rulers.

The choice of an Egyptian name attests to the fact that the Hittites were originally strongly influenced not only by the Sumerians, as we have seen, but also by the Egyptians.

Conclusion on the list of Hittite hieroglyphic signs

We can see that Hittite signs do not contain all the categories of prehistoric signs, like proto-cuneiform.

As with the other ideographic languages we’ve analyzed, we can also see that quite a number of categories are represented, with signs that are clearly similar to those already found in proto-cuneiform.

Even if it is rather late, it seems likely to corroborate the reading of certain prehistoric signs in support of proto-cuneiform, all the more so as the Hittite empire was in the area of influence of cuneiform and therefore of Sumerian and Akkadian religious culture.

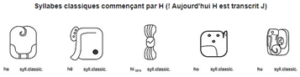

By way of illustration: the Hittite syllabary in cuneiform

Hittite cuneiform script is a variant of Akkadian cuneiform from the Paleobabylonian period, developed by the Hittites, a population of Indo-European origin attested in Anatolia (Turkey) between the 17th and early 12th centuries BC.

In addition to expressing the Hittite language, this script was also used by scribes for other languages such as Louvite, Palaite, Hatti, Hourrite, Akkadian and Sumerian[62] .

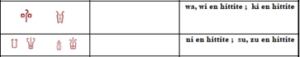

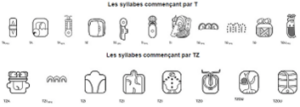

I therefore find it very interesting to provide you with a Hittite syllabary of cuneiforms with a phonetic value (called phonograms or syllabograms) of the type Vowel and Consonant + Vowel[63] :

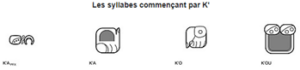

Hittite cuneiforms and animal signs

Why is this interesting?

As you’ve no doubt noticed, the cuneiform signs in this syllabary often represent animal forms (cow, dog, horse, bull, etc.) which refer to specific syllables.

Here are the main animal forms that can be identified:

e = = two animals in a row

da = = a cow

de = = a dog

ta = = a horse (injured?)

ga = = a bull (wounded?)

ka = = a pair of horned animals

ma = a cow or goat

ya = two animals side by side

wa = an animal without a body

ša = a (wounded?) dog

What’s crucial to understand in relation to the subject at hand – cave signs, which, as we’ve seen, are often associated with animal figures to such an extent that the archaeologists quoted wonder to what extent these animals are not themselves an integral part of the semiological system – is that these animals in cuneiform form each refer to a sound, a phoneme, a syllable.

This allows us to visualize the concept particularly well.

I haven’t gone further in the later Hittite Louvite hieroglyphs, but they also contain numerous animal forms to express a sound.

I won’t dwell here on the different syllables to which these animal signs refer (da, ta, ga, ka, ma, wa, ša), as we’ll have plenty of opportunity to explain the meaning of these different Sumerian logograms, but I can simply tell you that there is a strong correspondence between this Hittite syllabary and the literal or symbolic meanings of Sumerian, which attests to a strong cultural connection between the two peoples.

Other important signs:

Note also these signs to say:

lu = = a 3*3 crosshatch

mé = or mi

= a dead woman

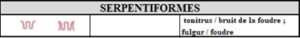

The list of Mayan script signs (- 300)

I include Maya ideographic writing in this comparative analysis, not because it is of major interest for deciphering cave signs, but simply because it was cited in the Sauvet / Wordarczyk essay as using one of the three methods of composing complex signs (juxtaposition, superposition, integration), in this case, integration.

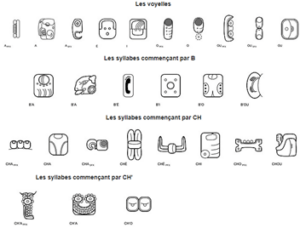

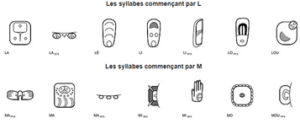

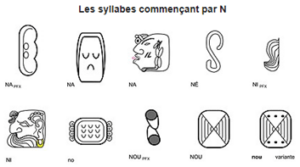

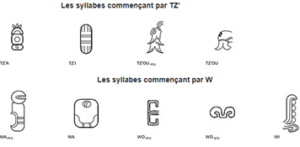

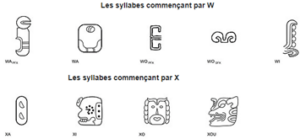

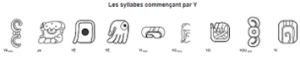

We’ll look at this a little later, but while we’re at it, the visualization of the Mayan syllabary, which is perfectly accessible, and which I submit to you here, shows very clearly that we are dealing with a completely different system of signs[64] .

In terms of geometric typology, we find essentially only squares, ovals, dots, lines and clafivorms (ché, cho, wo), but apart from these forms, it doesn’t seem to me that other categories of prehistoric signs are represented.

The Mayan syllabary

Conclusion on the list of Mayan hieroglyphic signs

Mayan hieroglyphs do not contain all the categories of prehistoric signs like proto-cuneiform.

Being much further back in time and space than its predecessors (with the exception of Olmec, of course), this script is unlikely to corroborate the reading of certain prehistoric signs in support of proto-cuneiform.

This doesn’t mean, however, that the mysticism wasn’t the same, as we’ll see in subsequent books how South American cults were totally in line with the celebration and representation of the original myth, but for all that, their semiological system resorted to a sign system of their own, very different from the primordial one.

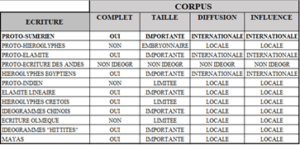

Intermediate findings from the analysis of lists of different archaic or ancient ideographic languages

The most archaic, the most complete, the most influential: proto-cuneiform

From this comparison, a first observation emerges:

Of all the oldest ideographic scripts (proto-cuneiform, proto-hioglyphics, proto-Elamite, proto-Indian), the oldest, paradoxically, is the one for which we have the largest, most widely distributed corpus, with a list of signs that is at once the most archaic (- 3,500), but at the same time very complete (which is not the case for proto-hioglyphics, which were embryonic at the time).

This explains its great domination at the time of Uruk and its influence over all the neighboring regions of the Middle East (Upper Mesopotamia; Syria; Elam, Southeastern Anatolia), which meant that all other scriptures could not compete on the same terms.

The very fact that it is difficult in some cases to draw up a complete list of signs for certain scripts attests to their much lesser diffusion, their much lesser aura, which necessarily places them qualitatively well behind proto-cuneiform as the best point of comparison.

Clearly, this simple and rapid comparison of these lists of signs, I believe, already makes it clear that if the referent archaeologists had done so, instead of dismissing ideographic scripts from their theoretical field of research on the pretext of a few ideograms that resemble each other but have “different meanings”, they would have immediately seen that not only are they not at all the same, but also and above all that proto-cuneiform corresponds to all categories of signs, from the simplest to the most complex.

They would also have realized that, even if other ideographic scripts are a long way from ticking all the boxes like proto-cuneiform, there are nevertheless recurring analogies between signs of ideographic scripts close in time and space, In particular, between proto-cuneiform and hieroglyphs, proto-Elamite, proto-Indian and linear Elamite, analogies that should corroborate the meaning already obtained by proto-cuneiform, or even explain certain signs that it would be unlikely to make. There are also analogies, albeit to a lesser extent, with more distant scripts in time and/or space (Cretan, Ossecail Chinese, Olmec, Hittite).

It is therefore important to understand that if we accept (at last!) the idea that proto-cuneiform is the main key to reading prehistoric signs, it’s also logical to think that languages that are temporally and geographically close, or even semantically and culturally very close, to proto-cuneiform (such as Egyptian hieroglyphs) could prove useful in corroborating the deciphering made possible by proto-cuneiform, or even, in certain cases, deciphering prehistoric signs.

Here are two simple tables summarizing the facts:

Comparative analysis of the rules of each semiological system

In the first major part of the comparative analysis between ideographic scripts, we compared corpora and lists of signs.

In this second major section, we’ll compare the rules of the prehistoric sign system identified by leading archaeologists as markers of a fully-fledged semiological system, with those we can observe in the ideographic scripts we’ve already referenced.

These rules are :

- Sign associations with animal signs

- Rules for forming complex signs

- The rules of syntax and, more specifically, the rules of incompatibility between signs.

We’ll see that if their analysis had been carried out seriously, comparing not only corpora and lists of signs, but also these rules, they would have immediately identified proto-cuneiform as the ideographic script that ticked, if not all the boxes of their observed model, at least the vast majority of them, in a way that left no room for doubt.

The interpenetration of language between animal signs and signs can be found in proto-cuneiform

You may recall that one of the first observations made was that the signs interpenetrated recurrently (nearly 60%) for the 9 “major keys” with animal figures.

I haven’t counted the number of proto-cuneiform signs associating signs and animal figures, but it’s clear that these are present, albeit to a much lesser extent.

Let’s look first at the major animal signs of the proto-cuneiform and then at examples of how these combine with other signs:

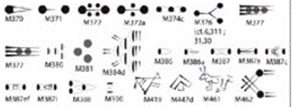

Examples of animal signs [65]

Here are the main examples:

[66] food: wild ram, bison, auroch; powerful[67]

or

[72] dara: billy goat, deer, fallow deer, mountain roe deer; ibex [73]

[74] anše: donkey, primrose, equine[75]

or

[80] mušen: bird (“sky reptile”)

[81] nam: area of responsibility, destiny, of a man of power (king, governor…)[82]

šah or [83]

sigga, sig, šeg: mountain wild boar [84]

Examples of sign associations with animal signs:

Now that the presence of animal signs has been attested, let’s take a look at the various ways in which the proto-cuneiform associates them with non-animal signs:

By superposition:

ga gu

Here, superimposing the animal sign of the domestic ox gu in the rectangle indicated ga gives the logogram ga gu

ga gu še [89]

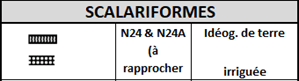

Here, superimposing the animal sign of the domestic ox gu in the rectangle indicated ga and with the addition of the scalariform (to use archaeologists’ terminology) še on the left side of the rectangle gives the logogram ga gu še

[90] a-ab(ba) lake, sea[91] (with namesake: father, elder, ancestor[92] …)

Here, superimposing the cow sign ab in the sign a

already seen gives the logogram a-ab[93]

lagab ku [94]

Here, superimposing the sign of the fish ku in the simple circle lagab gives the logogram lagab ku

ga gir

Here, superimposing the animal sign for gir fish (but also cow/mare) in the indicated rectangle gives the logogram ga gir.

ga gir ku

Here the superimposition of the two animal signs of fish gir (but also cow/mare) and ku in the indicated rectangle gives the logogram ga gir.

By juxtaposition :

gir še

Here, the juxtaposition of the še branch located here at the level of the right ear of the cow/mare(/fish) gir sign gives the logogram gir še

dara kar [98]

Here the juxtaposition of the animal sign dara and the “scalariform” kar

gives the word dara kar.

ku giš [99]

Here the juxtaposition of the fish sign ku and the flat rectangle giš gives the logogram ku giš

mušen pap[100]

Here, juxtaposing the mušen bird sign with the pap rectangle gives the compound logogram mušen pap.

Animal signs in other ideographic scriptures and their association with other signs

There’s nothing to suggest that the animal signs found only in proto-hioglyphs, proto-Elamite, Egyptian hieroglyphs, Cretan hieroglyphs, Chinese ossecaille ideograms and Hittite (Louvite) hieroglyphs are associated with any other hieroglyph/ideogram other than by simply writing the signs one after the other.

I invite you to consult the various databases cited for each reference that attests to this state of facts.

In none of these scripts are animal/non-animal signs superimposed or juxtaposed to form a complex sign, as in proto-cuneiform, which is also a feature of cave signs.

Proto-cuneiform findings

As a result, from this point of view too, proto-cuneiform is the one and only semiological system to match that of cave signs.

The 3 rules for composing complex signs

In addition to the existence of animal signs and complex animal signs, our referring archaeologists have also observed that the cave semiological system used three distinct and specific methods to create compound signs from simple signs: integration, superposition and juxtaposition:

Let’s see if the rules for creating prehistoric compound signs can be observed in proto-cuneiform:

Integration

As a reminder, here are the examples cited by archaeologists for the integration of signs:

You’ll see that, for example, dots are used in prehistoric signs to represent other signs such as the oval.

Examples of proto-cuneiform

However, there are numerous examples in proto-cuneiform that attest to the use of exactly the same ideogram formation process.

Here are “a few” with the pattern of dots or clouds of dots:

[101]

[102]

[103]

[104]

[105]

[106]

[107]

[108]

[109]

[111]

[112]

[113]

[114]

[116]

[117]

[118]

[119]

[120]

[121]

[122]

[123]

[124]

[125]

[126]

[127]

[128]

[129]

[130]

[131]

[132]

[133]

[134]

[135]

[136]

[137]

I think these many examples are self-explanatory.

Other ideographic languages and integration / Findings

It’s important to realize that this process is truly unique to proto-Cuneiform.

It is not found in any other script. This sumerian process is highly characteristic, in that it strictly reproduces the very same process used in prehistoric signs.

It’s a true semiological signature.

I’d like to add that when the authors say that Mayan writing resorts to integration, I don’t see how? As we shall see, it uses juxtaposition, but not integration.

As for the significance of these clouds of dots associated with an ideogram, I presume it serves to evoke, connote the end, death, finitude, disappearance of the concept evoked by the ideogram, the cloud of dots being, I think, a representation of its transformation into dust.

Overlay

As for the superposition rule, archaeologists illustrate it with the following examples:

We’ve already seen this principle of superimposition implemented between animal signs and other signs.

Examples of proto-cuneiform

Here are some other examples of proto-cuneiform ideograms:

With dots superimposed on the signs :

[138]

[139]

[140]

[141]

[142]

[143]

[144]

[145]

[146]

[147]

[148]

[149]

[150]

[151]

[152]

[153]

[154]

[155]

[156]

[157]

[158]

With short strokes superimposed on the signs :

[159]

[160]

[162]

[163]

[164]

[165]

[166]

[167]

[168]

[169]

[170]

[171]

[172]

[173]

[174]

[175]

[176]

[177]

[178]

[179]

[180]

[181]

[182]

[183]

[184]

[185]

[186]

[187]

[188]

[189]

With signs other than dashes and dots:

For examples of juxtapositions, simply review those cited above under the heading: Examples of sign associations with animal signs.

These are just a few examples with animals, but the list of signs is full of complex signs that are the juxtaposition of two signs, each with its own meaning taken in isolation.

For more details, please refer to the two files cited as sources for the list of proto-cuneiform signs.

Other ideographic languages and overlapping / observations and findings

Ideographic languages that can use this method

When it comes to superimposing signs such as lines or dots inserted into another sign, this method is used quite frequently in :

- Proto-Elamite (full dots, dashes and signs)

- Linear Elamite (dots, dashes, a few whole signs)

- Egyptian hieroglyphs (dots, episodic strokes; no whole signs)

- Proto-Indian (dots, episodic lines; some whole signs)

- Cretan hieroglyphs (dots, dashes, but also some whole signs)

- Chinese ossecaille ideograms (dots, lines, but not whole signs)

- Olmec ideograms (dots, lines, but not whole signs)

- Hittite hieroglyphs (dots, lines, but also some whole signs)

- Mayan ideograms (dots, lines, but not whole signs)

Particularities of certain languages, including proto-cuneiform

From what has just been said, however, it should be noted that the dots, dashes, etc. used in Egyptian, Cretan, Hittite, Chinese and Mayan hieroglyphs… are primarily intended to refer to comprehensible figures such as animals or objects, thus representing a pictogram (even if the meaning of pictogram is inappropriate, as it implies pronouncing the name of the designated object/animal), whereas in the others there is no such effect or intention.

Thus, only Proto-Cuneiform, Proto-Elamite, Linear Elamite and Olmec make use of these points/traits without seeking to evoke a specific animate/inanimate.

The only languages with real signs

In addition, it should be noted that the only scripts to juxtapose real signs, i.e. signs which, when taken in isolation, have a specific meaning of their own, are :

- The proto-cuneiform (very numerous; see the documentation cited as a source for the list of signs; see also the examples of animal-sign associations)

- Proto-Elamite (also apparently quite common; cf. comparison by F.Desset)

- Linear elamite (a single sign

or perhaps a few others?)

- Proto-Indian (a single sign

or perhaps a few others?)

- Hittite hieroglyphs (a single sign

or perhaps a few others?).

In Cretan, for example, we find the sign representing an eye, except that in Cretan the oval alone has no meaning of its own, whereas in proto-Cuneiform it does.

In the first case, it’s not a compound sign, but a representation of the eye, whereas in the Sumerian case, the underlying double meaning of the oval is played out by adding strokes.

Overlays

From what we’ve just said, it’s clear that only proto-Cuneiform (and perhaps even proto-Elamite) used this highly unusual process on a very regular basis, and that after 300 / 400 years it became almost anecdotal in the other scripts that appeared.

Finally, you won’t have failed to notice that in proto-cuneiform, not only is the principle strictly the same and highly represented, but if we take the examples taken by the reference archaeologists, we find exactly the same first three prehistoric signs cited!

Juxtaposition

As for the juxtaposition rule, archaeologists illustrate it with the following examples:

Archaeologists’ examples

We’ve also seen this process at work between animal signs and other signs.

Examples of proto-cuneiform

Here are a few examples that speak for themselves:

The fish

These four signs signify sukud: to be elevated, to shine (terminology used recurrently for the great divinity; we will have ample opportunity to verify this); a fish[194] (here too a symbol par excellence, as we shall see, of the great divinity).

The triangle and the branch

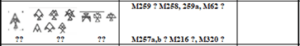

Here are a few examples of complex proto-cuneiform signs juxtaposing/associating the branch with other signs:

[195]

[196]

or

[197]

[198]

[199]

[200]

[201]

[202]

[203]

Note that the first two are very similar to the prehistoric sign!

So we have not only the same principle of composition applied to signs, but also the same natures of signs.

It should be pointed out, however, that and

do not have the same meaning in proto-cuneiform, and it is necessary to determine which of the two the prehistoric sign

refers to.

Other ideographic languages and juxtaposition / observations and findings

If by juxtaposition we mean the touching or juxtaposition of two signs, each of which has its own meaning when taken in isolation, and in a given direction, for example from right to left or left to right (as in the example ) or from top to bottom or bottom to top (as in the example

or even

), we can say that this process is present in all ideographic scripts.

In fact, since the function of each sign is either to refer to a sound (phonogram or syllabogram), or to a concept (ideogram), or to the animate/inanimate it represents (pictogram), all three invariably leading to the pronunciation of a more or less short logogram (a letter, a word of one or two or more syllables), making them touch or simply abut each other produces sequences of words and therefore ultimately a sentence.

From this point of view, it’s the same process we use to write, putting letters one after the other and in groups. I’m talking here only about the process, not the semantic system, since ideographic signs and letters of the alphabet do not, of course, have the same function.

If, on the other hand, by juxtaposition we mean the fact that one sign can be associated with another sign in a way as particular as where the two signs recompose another sign, without any particular orientation in space, then we are faced with a method that is only used by :

- The proto-cuneiform in an extensive way (cf source CNIL ex. p. 2

p.4

p.6

etc.).

- Proto-Elamite, too, no doubt (cf. examples of patronymic signs:

).

In other ideographic languages, on the other hand, signs follow one another in one direction or another and do not touch:

- Including in Egyptian hieroglyphics (where, apart from the determinative placed at the extreme right, the signs follow one another and are read from left to right; they are also sometimes placed one on top of the other, in which case the top sign is read first),

- including in Chinese and Mayan writing, where the juxtaposition of different phonetic signs to make up a complex sign is done in a non-random way, but may respect an invariable and predefined reading direction.

Observation for juxtaposition

From what we’ve just said, it’s clear that only proto-Cuneiform and even proto-Elamite apply this method of juxtaposition in the same way as prehistoric signs, with signs that juxtapose, touching each other, without having a given spatial distribution.

Conclusion for the comparative analysis of complex sign composition rules (integration, superposition, juxtaposition)

Remember what archaeologists have said on the subject of complex sign formation: that these assembly processes (juxtaposition, superimposition) exist in Chinese writing, and are even integrated into Mayan glyphs…

As we have seen, this observation is really very incomplete.

But the important thing is not to draw attention to their mistakes, but to what this deeper comparative analysis tells us:

Fundamentally, that proto-cuneiform is THE ONLY script to apply each of these three methods of composition. Integration is its signature. Superposition and juxtaposition are its domain, along with proto-Elamite.

It combines not one, not two of these three means of composing complex signs, but all three!

And what’s more, extensively.

Finally, to crown it all, simple signs and compound signs are of the same nature, or even strictly equivalent!

What conclusions do you draw?

Probably the same as mine.

After examining the lists of signs, could this be a second incredible succession of coincidences?

But that’s not all.

We’ve just covered the rules for composing complex signs.

Let’s take a look at the syntax rules.

Comparative analysis of syntax rules

Preliminary observations on the biases of a strictly statistical and geometric approach

The biases of a purely statistical approach

Before moving on to a comparative analysis of the rules between the two semiological systems, it is first necessary to understand that the two lists of signs being compared are necessarily different:

By their timing

Indeed, even if I name the prehistoric signs as proto-cuneiform, i.e., one might understand, the same as Uruk, it’s obvious that between the time these signs were affixed or engraved and Uruk there were simplifying stylistic divergences.

That’s why it’s probably more important to say that the proto-cuneiform used in the caves is a more archaic form than the entire list of signs of proto-cuneiform as we know it. That’s why I call cave sign language pre-proto-cuneiform.

By the probable selection of signs made by local priesthood

It’s also quite logical that certain signs have been prioritized by those living in one geographical area rather than another. The language remains the same, but not necessarily the signs chosen.

The best example of this is the Zatu sign, a sign of death (and also, as we’ll see in the section on decryption, a sign of rebirth) which has 235 forms of writing! It occupies 47 pages of signs out of 346 pages of signs in the CNIL lexicon[204] . I’m taking an extreme example here, as it’s the only sign with so many possible representations, the others averaging no more than 4 or 5 possible variations. This is obviously linked to the deep symbolic and cultural significance of the zatu sign, which we’ll examine later. Indeed, the proto-cuneiform language is sometimes referred to by some as the language of “zatu signs”, because of the extreme importance attached to this specific zatu logogram.

But this helps us to understand that it’s not necessarily all the zatu signs that we’ll find in the cave sanctuaries, but perhaps only a minority of them, with each of them expressed perhaps several times over. Even if, from a statistician’s point of view, this would tend to make them appear more important than the others, especially as many probably didn’t even appear, the latter being therefore considered non-existent, from a linguistic point of view on the other hand, no zatu sign is more important than another, since they all have the same meaning.

It’s simply the fact that some were chosen and not others that gives them greater and real importance than the others, but this is a statistical bias based solely on the material recovered.

By selecting the right sign for the right medium

By the same token, in addition to the fact that prehistoric man may have been inclined to use only those signs to which he was more accustomed culturally, it is also entirely understandable that prehistoric man also favored signs that were easier to produce than others, depending on the nature of the support he used and the mode of representation (drawing, engraving, etc.).

For example, it is easier to draw this than this

.

Yet these two zatu signs mean exactly the same thing.

If you know all the Zatu signs, it’s likely that you won’t use them all, but that some of them, probably the simplest to execute (even if this won’t be systematic, depending as we said above on the importance of each sign in the community in which you live, which also favored complex versions) will be used.